Cartilage Restoration

Cartilage is the shiny substance that covers our bones at the joints and allows our joint to slide smoothly across one another without pain. Cartilage can degenerate over time or from a discrete injury which can become cause increased friction and stress resulting in swelling and pain. If that damage is diffuse it is called arthritis which simply means the generalized degeneration of cartilage. There is no cure for this currently. However, focal or discrete cartilage lesions can occur which can be treated surgically, termed cartilage restoration procedures. While many people are not candidates for this due to a more diffuse degeneration, many can benefit from these procedures.

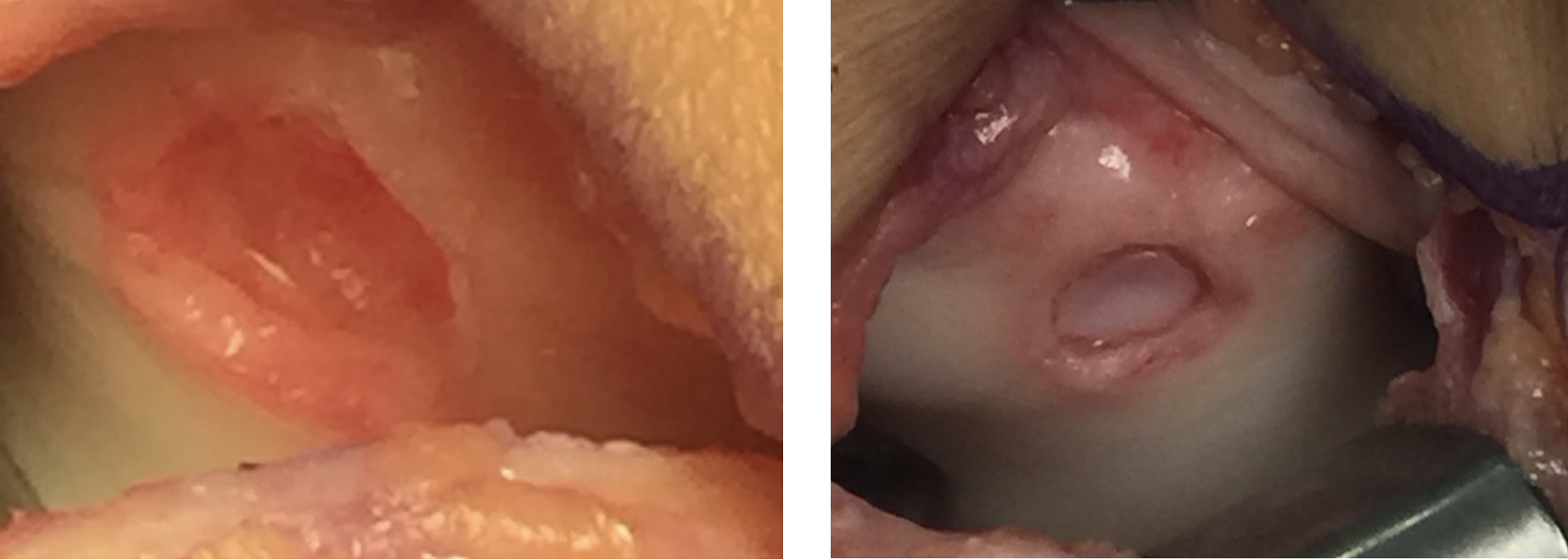

Full thickness cartilage defect.

Microfracture

There are several different types of cartilage restoration. The most basic is called a microfracture during which the surgeon places several holes in the cartilage defect. This produces healing fibrous tissue similar to filling in a pot hole in a road. This has largely fallen out of favor due to poor results with large defects and degeneration of the tissue over 5-7 years. However it has good results with smaller defects and should not be abandoned completely.

Micro Fracture.

Allograft Cartilage Cells

There are different types of these cells but the basic premise is the same. The surgeon essentially performs a microfracture and then adds the allograft (cadaver) cells to it and place a covering over it. This has better results than microfracture alone but long term studies are somewhat lacking at this point. Like microfracture it can be performed as a single stage procedure which makes it a nice option for smaller lesions.

Matrix Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI)

This procedure is generally regarded as a step up from allograft cartilage cell procedures as it involves the patient’s own cartilage cells rather than a cadaver which theoretically grow better cartilage that is more durable. Because of this it requires two stages or procedures. The first involves harvesting a small amount of cartilage from an area of the joint that is non-articular or not used by the body. The cells are then sent off to a lab, grown in the lab and placed onto a medium for attachment and further growth in the body. About 6 weeks later (or anytime after that) the cells are re-implanted in the body with a collagen cap enclosing them. Over time the body incorporates the cells and potentiate them into regular cartilage. There are many good long term studies demonstrating sustained success with this technique. This can be used for defects anywhere in the knee but is especially good for patellofemoral (areas involving the knee cap (patella) or bone underneath the patella (trochlea).

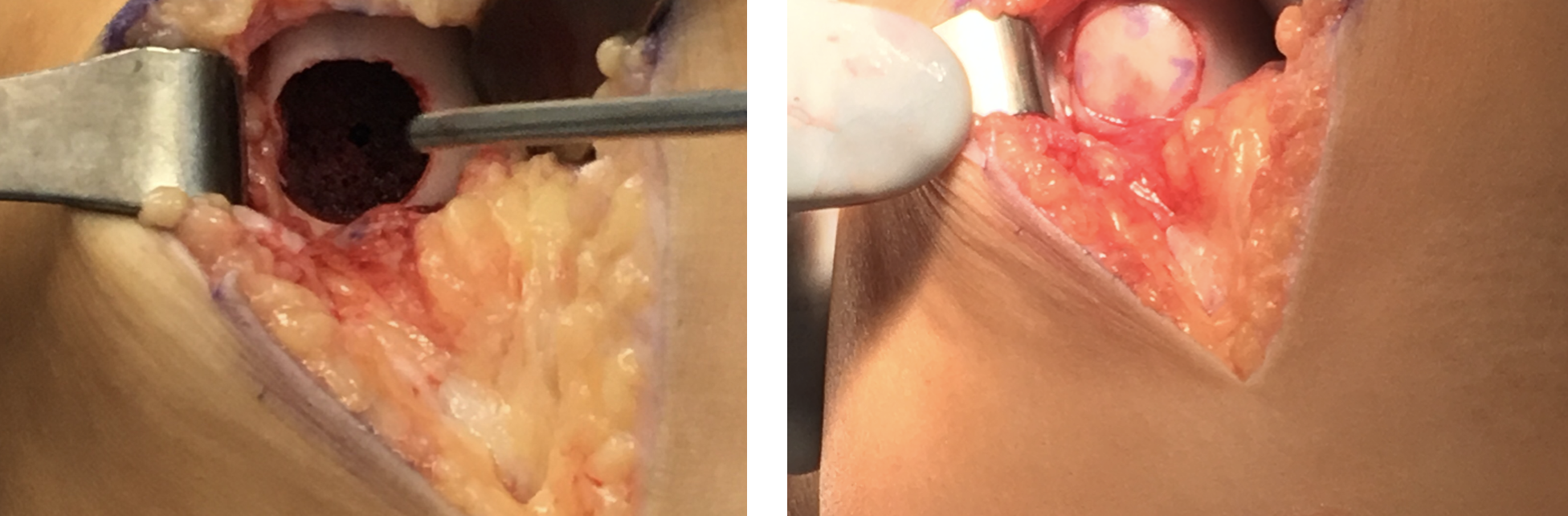

Chondral Defect Trochlea (left). Defect after MACI and PATCH implantation (right)

Osteochondral Autograft

This is a single stage procedure during which the surgeon fills the cartilage defect with a plug of cartilage and bone from the patient’s own knee and places this plug into the defect after drilling a hole into the defect that matches the same shape and depth as the plug. The plug is taken from an area of the knee that is non-articulating or not used. Because of this it is best used for small defects only as there is not a large portion of cartilage in the knee that is non-articulating Long term results are good with small defects.

Osteochondral Allograft

This can also be a single stage procedure provided the surgeon is sure the patient is a candidate. It is best used for large defects in the condyles (ends of the femur or thigh bone). It involves matching the patient’s defect region with a cartilage plug from a cadaver similar to osteochondral autograft. However, it is much more versatile than the autograft as the surgeon is using a cadaver so a much larger plug can be used without worry about damaging anything as it is a cadaver knee rather than the patient’s own cartilage. The surgeon can also match the topography and geometry of the knee much easier since the plug is taken from the same exact area on the cadaver that is damaged on the patient rather than a portion of the patient’s knee cartilage that is non-articulating or not used (again since this area is fairly small).

Cartilage defect prior to allograft (left). Defect following implantation of the allograft (right).

In general all of these options have their place. Dr. Postma will have a discussion with you regarding which is the best option for you as each surgery is tailored to the patient’s specific needs for function and recovery.